To be perhaps a bit over-simplistic, I see a few distinct ways in which low socioeconomic status can manifest itself into real barriers to achievement. First is a simple lack of resources, which tends to be the focus of many interventions to assist those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. It's undoubtedly a major problem - if some people can pay for things that others can't, and those things either directly or indirectly lead to personal achievement, then wealthier individuals will naturally benefit over their less-wealthy counterparts. In medicine these lead to some obvious and not-so-obvious barriers. To get into medicine, a student needs to pay for their undergraduate education, the MCAT, application fees, travel to interviews, and interview attire. These are not small expenses, especially when added together. However, that's just the bare minimum. Things money can buy that aren't necessary, but very helpful for getting into medical school include taking extra courses or second degrees (or even doing medical school outside of Canada), taking various prep courses or receiving extra tutoring, spending more time on unpaid extra-curriculars, or even paying for certain extra-curriculars.

Yet these examples hit only the "economic" portion of socioeconomic status. To get into medical school, there is also a significant social component that I don't believe gets recognized as often as it perhaps should. One is the development of baseline skills that many people take for granted. To use an extreme example, if a person was never taught how to read, they won't get into medical school, no matter how intelligent, responsible, and personable they might be. They can, of course, learn how to read and then start to move towards medicine, but it's a difficult skill to learn in adulthood and fundamental to all the steps that come after it. It's also a skill that typically requires significant support from others. We're lucky that in Canada most people get that support as children, but there are other skills which are not provided as reliably by our primary or secondary education system. One that springs to mind is professional communication skills, which are sorely lacking in formal education. The ability to write a concise, polite, effective e-mail has enormous benefits in securing various opportunities on a path to medicine, yet this may not be a skill some individuals even see from their elders or peers if they grow up in a setting without business people or other professionals in their lives. It's a skill that can be developed, but this takes time, support, and a certain degree of trial-and-error that more initiated individuals will not have to go through.

Likewise, access to opportunities is far from equitable across individuals of different social status. One example that comes to mind is students who happen to have physicians as parents. These parents hear about or inquire about opportunities with their colleagues and provide a point of introduction for their children. These students must still show they are worthy of those opportunities and perform well once they secure them to advance further, but that first step is often a critical one. More importantly, opportunities create a snowball effect, where prior experience justifies acceptance to future opportunities, up to and including medical school. That is, individuals with higher social status and more connections can turn into seemingly more capable applicants - and may actually be more capable applicants - due to these connections, completely unrelated to ability or effort.

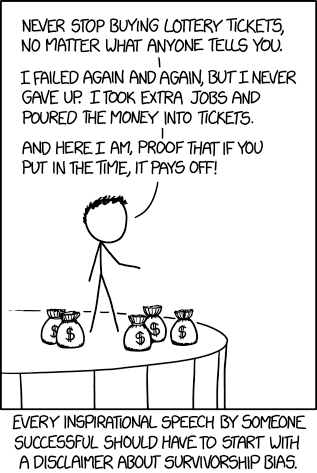

I'd like to emphasize that higher socioeconomic status does not remove the need for hard work or eliminate the role of a certain degree of natural ability in the process. Medicine, like many fields, is full of well-off individuals, but these people have nevertheless put in significant effort to get to where they are. However, what my recent experiences have reminded me of is that while hard work is necessary for success, it is not sufficient on its own, hence the title of this piece. Without trying to set up too much of a strawman, I think some well-off individuals give too much credit to their own hard work in achieving success, because they started to see success when they started putting in the effort. Yet these individuals started seeing success after they started to work harder towards success because everything else was already set up for them. I've met plenty of people who haven't had the same experience, where hard work perhaps improved their situations, but that improvement was limited due to factors beyond their control.

Bringing this back to the original point about the multifaceted nature of socioeconomic disadvantage for a minute, I now worry more that many interventions to improve such disadvantage are perhaps too simplistic to be effective. We can throw money at a problem but it can end up being a waste if the more social aspects to disadvantage are left unaddressed. On the flip side, we could try to improve these social elements, yet see minimal results if resources are still lacking. However, on a more positive note, this also means that there are many different ways we can make marginal improvements in peoples' lives. If we don't have money to help, we can volunteer time to teach new skills, or provide connections that might otherwise being lacking. If we're busy and running off our feet, financial supports can nevertheless be valuable. When people move up the socioeconomic ladder, patchwork systems of support like this can be an important reason why, allowing them to fully utilize their own natural talents and work ethic.

From a personal perspective, as I move forward within my own career in medicine, I'm hoping there will be more opportunities to level the playing field a little bit - and I hope I'll have the good sense to recognize when those opportunities arise.